Causal Inference: Part 1

This article is the first in a two part series that deals with the underlying concepts and mathematics of Pearlian causal inference. Part 2 will focus on a practical example using the DoWhy library. If you prefer to begin with implementation first, skip to Part 2 when it becomes available then return here for the theory.

Causality: Photo by Nadir sYzYgY on Unsplash

Causal inference has undergone tremendous growth in recent years. This surge has happened in parallel with the rise of Data Science (DS) more broadly, but they still remain distinct in practice. While the science behind causal reasoning has benefited from recent work by Judea Pearl, Donald Rubin, Susan Athey, and many more, the insights they found have not made their way into mainstream DS, despite readily available implementations of these techniques. Many DS practitioners simply do not know about or employ causal reasoning in their workflows and that may be for several reasons…

- The assumptions that go into causal reasoning, like Bayesian models, can be sliced, diced, and debated six ways from Sunday. (thanks to my Linkedin connection Gino Almondo for this insight)

- People think that correlations are automatically causal and are enough in themselves. Look for this in your workplace and you’ll be surprised how often it shows up.

- Causal inference is perceived to be hard. We don’t like hard.

These points have varying degrees of validity, but ultimately miss the main point. The main point is that while there are challenges, we have in our hand a set of concepts and techniques that if applied with care, will completely transform the way that data science is practiced and perceived. We get to leverage domain knowledge to make robust inference. Let’s first set up the discussion with some preliminaries.

What is Causal?

For this article, we will adopt the interventionist approach to defining causality. We all have an intuitive idea of what is causal, but to work in the language of mathematics we will need something more formal.

The definition is that for two distinct events A and B, A causes B if a change in A corresponds to a change in B, all else being equal.

Most of causal inference deals with ensuring the “all else is equal” part. There are other definitions that are similar, with vigorous debate surrounding which is most correct, but we will settle on this one and proceed.

How do we establish Causality?

Before the causal renaissance of recent times took place, the gold standard in establishing causal links was randomized experimentation. In many ways they still are. So let’s set the stage by discussing causality in the context of a randomized experiment.

We have an outcome we would like to measure, named Y. We want to see if manipulating a specific treatment X will cause appreciable change in Y. In a randomized trial, such as a drug test, we would obtain a sufficiently large sample (using power analysis) of people at random from the broader population. The participants would be randomly assigned either the drug or a placebo. We would then measure the difference in Placebo group and Drug group, which is called the Treatment Effect, which can be done in a variety of ways (see cohen’s d or CATE). Any effect sizes would then be from the treatment alone and not due to any other factors, or confounders, that may be present.

Random assignment ensures that “all else being equal” is true in the aggregate.

The Real World

Now we come to the main hurdle that we face in causal inference. We don’t always have the time and money to do randomized experiments to establish a causal link. Even when we do, it may not be ethical to do so. We may in the end just have a set of observational data, and a few hypotheses we have built from observation. Can we test them using our non-randomized data? The answer is yes, and that is where our new toolkit comes into play. The techniques we will use will take our observational dataset and transform it into what is called the interventional dataset, from which we can draw causal inferences. The key here is that the data itself is not enough to establish causality (see Simpson’s Paradox). We need more to reason robustly.

Given that the data is not enough, we will draw a literal picture of the world, called a causal graph, that encodes our assumptions about the data generating process. The data generating process is the system whose dynamics we are trying to understand. This will help us to construct our interventional distribution, and test whether our model is valid.

We are mirroring the scientific process. We start with a hypothesis, then we model how the world behaves under that hypothesis using our causal graph. Finally we test our model using the data, which may uphold the hypothesis or not. Additionally, we further test the model to see how sensitive it is to changes, unaccounted confounders, and other gotchas. Iterate until your theories fit the facts.

Going Deeper

Let’s define a few terms…

Intervention: Actively doing X leads to a change in Y.

Examples: If I push my punk brother, does he get mad? If I give a person the drug, does it make them better?

Counterfactual: What if I hadn’t done X, would Y have still occured?

Examples: If I hadn’t pushed my punk brother, would he have fallen down? If the patient had not been given the drug, would they have gotten better?

Reasoning with interventions and counterfactuals mirrors the normal, human approach to understanding causality. We are creating two different worlds and comparing the results in both. If we have an intervention case, and its counterfactual, we can establish causality. In a randomized experiment, we have those two readily in hand at the group level. When the level of analysis changes to the individual, then we realize one of the most fundamental problems we are trying to solve. We see that we have a missing data problem. We do not have the counterfactual in hand, because the counterfactual for an individual doesn’t exist. You cannot be both treated and untreated simultaneously. Twin studies come close. Thankfully, we have ways to estimate this counterfactual while controlling for everything that may muddy the waters (confound) of our analysis. Remember that we are trying to hold all else equal, which is why we need a counterfactual. Let’s dive into the math to understand what’s going on better.

Derivations

Lorem ipsum

When we obtain observational data, what we are getting are probability distributions, whether the data is discrete or continuous. The two main types are joint probabilities and conditional probabilities. Anyone who has taken a basic probability course has covered these topics, but they provide the basis for construction of our causal formulas. Below are two data distributions.

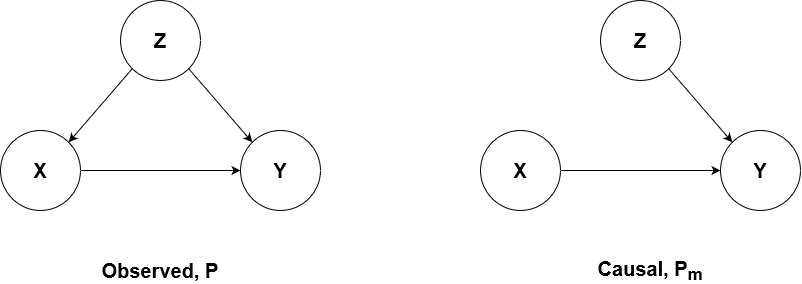

Observation and Intervention Diagrams

| On the left, we see the observed model which shows the interrelationships between the variables in our raw data. Given our definition of causality, we need to estimate the effect that changing X has on Y, independent of everything else. For our observed data, we are unable to make a change in X that would not also have corresponded to a change in Z, therefore changes in X are not indicative of causal changes in Y. We need a way to disentangle the confounding effect of Z on X, such that P(X | Z) = P(Z), or to put it another way, we need to MANIPULATE the observed data to make the two variables independent. We need to perform graph surgery. |

The figure on the right shows us our desired state, post-surgical state. Z and X are not connected and therefore a change in one does not affect the other. This is called d-separation. And since X is still upstream of Y, any change in X will result in a causal change in Y, whether X is changing spontaneously or by direct adjustment.

Assumptions

Now we move on to the derivation that allows us to transform our observed data distribution into our intervention data distribution. We start the derivation with three links between the two. We use P to denote our observational data distribution, and Pₘ to denote the manipulated, intervention data distribution.

Since the incoming effects of Y remain unchanged between the two graphs, the probability distributions are the same as well. This is our first invariance link.

The process determining Z does not change by removing the connection between Z and X. This is our second invariance link.

Z and X are d-separated in the manipulated model, and therefore are independent (having information about Z doesn’t tell us anything about X in the latter model). From link 3, it follows we can go one step further and obtain P(Z).

Given these links, we begin from the causal diagram on the right and define our do operator. We want to know, what is the probability of Y given that I intervene on X, denoted by do(X). It follows then that…

Next we expand the right side of the equation to account for Z

By the Law of Total Probability ,we are taking a weighted average of P(Y|X) over Z. This is how we control for the effect of Z. This is identical to Inverse Probability weighting and propensity score weighting techniques to control for confounding. Adam Kelleher has a great article showing the equivalence here, so definitely check it out if you’re interested in going deeper.

Next we use the principle of d-separation of Z and X to obtain

Finally we invoke the invariance link between the manipulated and observational distribution to get

Using this last expression, called the adjustment formula, we have now defined how we can generate our interventional distribution,

For our drug trial example which is a discrete binary outcome, estimating the treatment effect using our derived causal expression, we could define the Average Treatment Effect (ATE) as

Thus, we obtain the same outcome using a randomized trial as we do by controlling for all pertinent confounders (denoted as Z above).

The first term on the top is the observed treatment effect probability and the second is the counterfactual probability. Their difference, assuming Z stands for all confounders of Y and X, establishes the causal effect of treatment X on the outcome Y. Notice that Z could be either continuous or discrete itself, it does not matter. There is a beautiful flexibility apparent in the formulation.

Final Matter

Those are the basics of Pearl’s Causal Inference. For alternate discussion on causality, read up on Rubin’s Potential Outcomes Framework. If you like debates between genius scientists, this resource will make you happy. For an application of causal reasoning to high dimensional datasets using Random Forest, see Susan Athey’s recent work here. A great intro book by Amit Sharma and Emre Kiciman can be found here. Finally, read up on the backdoor criterion, an important next step in causal inference which can be read about here.

We have just scratched the surface of powerful concepts that really put the Science into Data Science. I hope this has been helpful to establish the theory before the implementation. I also hope that it has sparked your curiosity, so that you want to learn more and start to apply these principles in your work. Part 2 of this series will be a hands on application of Pearlian do calculus to a causal problem in the healthcare space using the DoWhy package.

Stay Tuned! Thanks for your time, and God Bless.